This article was originally published in Interest New Zealand which you can read here.

The latest OECD economic snapshot of New Zealand warned that despite a rebound in the second half of 2020, the economy was not yet on a firm footing.

They recommended the government swiftly implement the infrastructure spending component of the COVID-19 response package to underpin the recovery.

The reason for the urgency is that delays in spending risk being too late to play a part in the recovery and can actually be detrimental by overheating the economy. However concerns still remain about how quickly many of the so-called “shovel-ready projects” will get off the ground and if they do, how they fit into a national infrastructure strategy.

Global gap in infrastructure

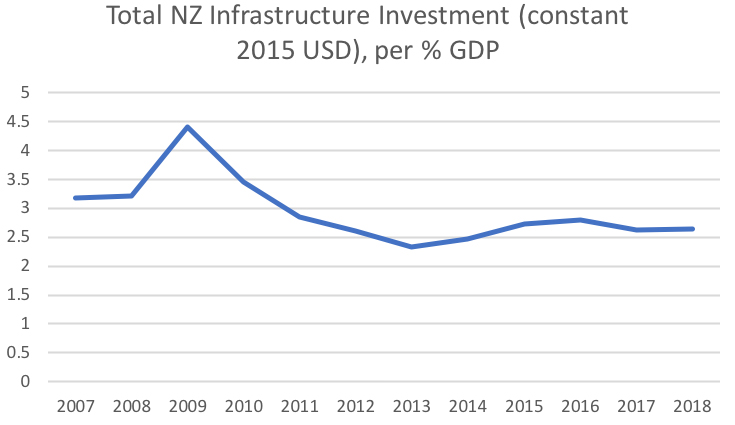

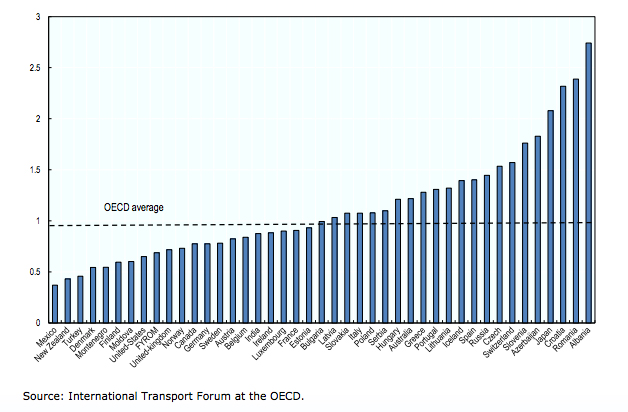

New Zealand has invested well below the OECD average in its core infrastructure assets over many decades. Frequent reports of congested roads, fatigued rail tracks, water shortages and burst sewage pipes are a clear demonstration of the impact of this underinvestment.

According to the OECD economic survey of New Zealand in 2019, this has been exacerbated by the fact that local governments have borne much of the infrastructure costs with limited opportunities to recoup these costs through user charging and rates increases.

Source: Global Infrastructure Hub

Investment in road and rail infrastructure as a share of GDP

(average 2000-2010)

However, New Zealand is not alone in facing an Infrastructure deficit. The Global Infrastructure Hub predicts a US$18 trillion gap between the projected investment and the amount required to meet required global infrastructure needs by 2040.

The reasons for the persistent underfunding are complex. In the developed world an aging population has strained government budgets due to increasing costs of healthcare and pension obligations. At a global level, the world’s infrastructure is struggling to cope with the twin forces of urbanization and population growth.

Benefits of infrastructure spending during an economic downturn

Infrastructure investment has long been recognised as critical to long-term economic growth and progress. A review of 200 studies over the last 25 years by Global Infrastructure Hub concludes government investment in infrastructure is more effective than other types of public spending in increasing economic output, particularly over the medium term. In the short term, it can boost demand and in the long term increases both GDP and productivity.

According to an IMF study, the biggest return from infrastructure investments occurs during recessions when the spending is debt-funded, so it is not surprising that many countries around the world are now investing heavily in their infrastructure to spur economic growth.

A solution to our lacklustre productivity performance?

As well as boosting economic growth, according to the US Economic Policy Institute, infrastructure investment can improve a country’s productivity performance. It does this by first creating a tighter labour market through creating new jobs. This can already be evidenced in New Zealand’s where the growth in construction jobs has largely offset the losses in tourism-related jobs caused by the pandemic. Secondly and more importantly, investment in infrastructure can significantly boost productivity by increasing the “public capital stock” or the country’s physical capital. The EPI review of multiple studies on the subject indicated that for each $100 spent on infrastructure private-sector output increased by an average of $17 over the long run.

Shovel ready projects?

As of 28 January this year 170 shovel-ready projects with a total funding value of 2.6b had been announced by the Infrastructure Reference Group. However, there is still a big gap between the committed funding and the total cost of the projects. There are also real concerns that there is a lack of strategy and vision for the infrastructure development will be costly for the country in absolute terms and in terms of growth.

Funding announcements are important for building confidence, but as Sir John Armitt, the chair of the UK National Infrastructure Commission cautions the most important role the government can play is in establishing a clear strategy for what they are attempting to achieve with the nation’s infrastructure “Clear objectives should help build consensus across political divides and ensure longevity, which, in turn, enables investors to orient their portfolios.”

The NZ Infrastructure Commission won’t have a draft strategy available for consultation until mid-2021. While a national infrastructure strategy will be a welcome development, whether it will be in time to play a role in New Zealand’s post-COVID recovery is still unclear.